Coral Sea

Battle of Coral Sea - 4 to 8 May 1942

This marked the first air naval battle in history as none of the carriers or surface vessels fired at each other. The planes from both sides were able to take off from their decks to do the battling.

In early 1942, as the list of military defeats and reversals for the allies military and naval forces began to mount, the feeling in the general populace of Australia was one of depression and a general expectation that the Japanese would invade at any moment. The Japanese were, by April 1942, examining the possibility of capturing Port Moresby, Tulagi, New Caledonia, Fiji and Samoa. The object of this plan was to extend and strengthen the Japanese defensive perimeter as well as cutting the lines of communication between Australia and the United States. The occupation of Port Moresby, designated Operation MO, would not only cut off the eastern sea approaches to Darwin but provide the Imperial Japanese Navy with a secure operating base on Australia's northern doorstep.

The Japanese plan

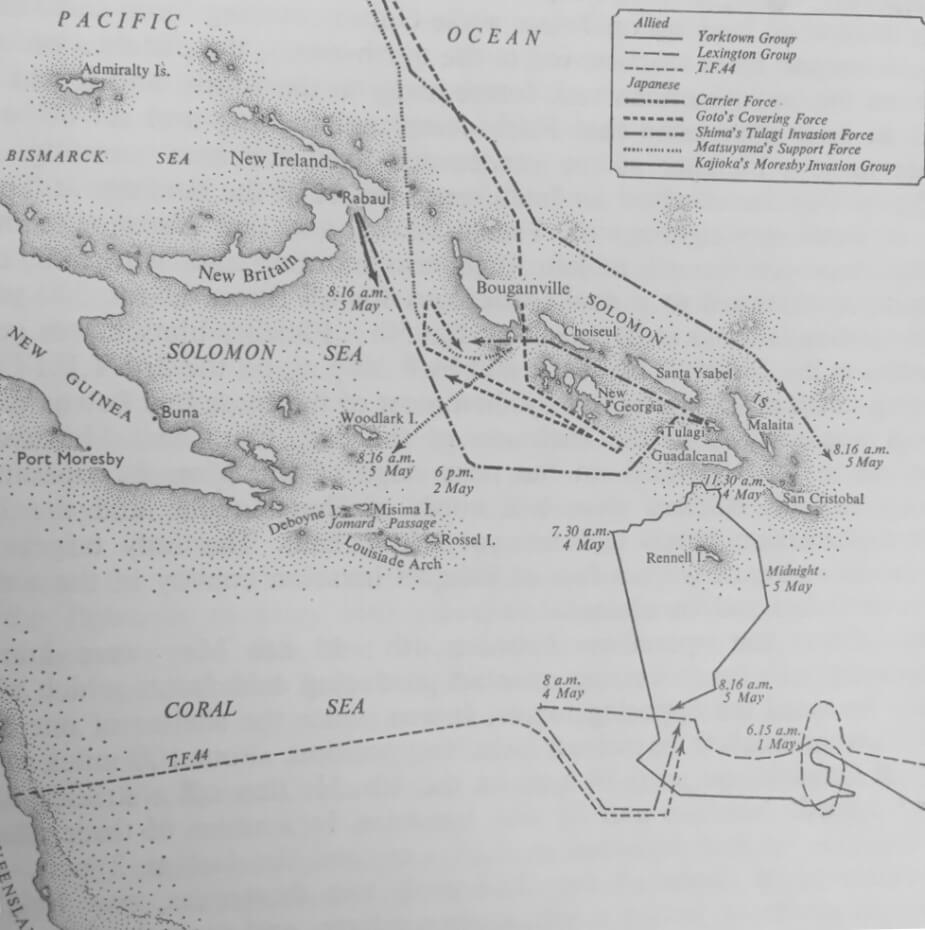

The Japanese plan was to initially seize the islands of Tulagi, in the Solomons, and Deboyne off the east coast of New Guinea. The intent was to use both islands as bases for flying boats which would then conduct patrols into the Coral Sea in order to protect the flank of the Moresby invasion force. The Japanese also believed that they would be denying the Americans the use of these islands for the same purpose. The Moresby occupation force would sail after the capture of Tulagi on 3 May. As the Moresby occupation force entered the Coral Sea from the north it would be covered by the Carrier Striking Force which would enter the Coral Sea from the direction of the Solomon Islands. Prior to implementation, the operation was expanded to include the seizure of Ocean Island and Nauru after the capture of Port Moresby.

American intelligence on Japanese intentions

Prior to the fall of the Philippines the United States Navy’s (USN) signals intelligence unit at Corregidor Island had been transferred to Melbourne and became a joint USN/RAN unit known as Fleet Radio Unit Melbourne. This organisation was to play an important part in the Battle of Coral Sea and in the Battle of Midway and indeed the entire war in the pacific.

As a consequence of the ability to read Japanese naval communications traffic the Americans were almost as well informed on what was planned as the Japanese commanders. The problem was in the correct interpretation of that information. Armed with the information on the movements and intent of the Japanese the Allies were able to concentrate much of their limited available striking forces in the Coral Sea area.

Coral Sea Battle

When the Japanese landed at Tulagi on May 3, carrier-based US planes from a task force commanded by Rear Adm. Frank J. Fletcher struck the landing group, sinking one destroyer and some minesweepers and landing barges. Most of the naval units covering the main Japanese invasion force that then left Rabaul, New Britain, for Port Moresby on 4 May took a circuitous route to the east.

On May 5 and 6, 1942, opposing carrier groups sought each other.

The US commander made a risky decision and sent a cruiser group without air cover to cover the Jomard Passage and intercept the invasion force as it exited. This group including HMA Ships Australia and Hobart was spotted and attacked by Japanese planes. On their return to Rabaul the airmen reported they had sunk a battleship and damaged a second and a cruiser. This inaccurate report later helped result in the invasion force reversing course till the battleship sighting was clarified.

On the morning of 7 May Japanese carrier-based planes sank a U.S. destroyer and an oiler. Fletcher’s planes sank the light carrier Shoho and a cruiser.

The next day Japanese aircraft sank the carrier USN Lexington and damaged the carrier USN Yorktown, while US planes so crippled the large Japanese carrier IJN Shokaku that it had to retire from action. So many Japanese planes were lost that the Port Moresby invasion force, without adequate air cover and harassed by Allied land-based bombers, turned back to Rabaul.

The aftermath

Both the Japanese and the Allies have portrayed the Battle of the Coral Sea as a victory. In a sense they are both right.

On the Japanese part they managed to sink more American ships than they lost, while the Allies not only prevented the Japanese from achieving their objective, the occupation of Port Moresby, but also reduced the forces available to the Japanese for the forthcoming Midway operations.

Against this, on the part of the Americans, must be weighed the fact that the Japanese assault forces remained intact and all that had actually stood in the way of the Japanese and the capture Port Moresby were the cruisers. Fletcher’s carriers, which were engaged in trying to locate and destroy the Japanese carriers, were too far away and too busy to provide any opposition or support if required. The decision by Fletcher to weaken his forces by detaching the cruiser force had proved to be the correct one, even though this may have contributed to the loss of USN Lexington.

The Royal Australian Navy’s overall contribution to the Battle of the Coral Sea may not have been as spectacular as that of the American carriers, but the work done by the coast watchers, intelligence staff, the cruisers and other support ships and personnel all contributed to the final result, not just at the Coral Sea but throughout the Pacific War. While Australians today may scoff at the fears of a Japanese invasion during 1942 the fact is that for many Australians during the 1940s that fear was real.